The role of members of the Muslim population in the Genocide against Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) has, to this day, remained without proper analysis. Nevertheless, over the past thirty years, several collections of documents and historical studies have been published that shed light on this issue as well. On the other hand, official Sarajevo, along with the professional and especially lay public, denies any significant Muslim involvement in the Genocide against Serbs in the NDH. There are even those who justify Muslim crimes against Serbs. In some cases, descendants of Muslim perpetrators from the NDH era openly express pride in their ancestors who killed Serbs. The most recent example of this can be found on the „Forgotten Roots“ page (Заборављени коријени), where a discussion emerged regarding the crimes committed at Garavice near Bihać. In the comments, several descendants of Muslim perpetrators publicly stated that they are proud of their grandfathers and that such crimes could happen again. In addition, many Muslim residents of Bihać appeared in the discussion to deny that the local Muslim population played any significant role in the mass killing of Serbs at Garavice. Therefore, there is a clear need for further research and greater emphasis on the role that segments of the Muslim population played in the Genocide against Serbs in the NDH.

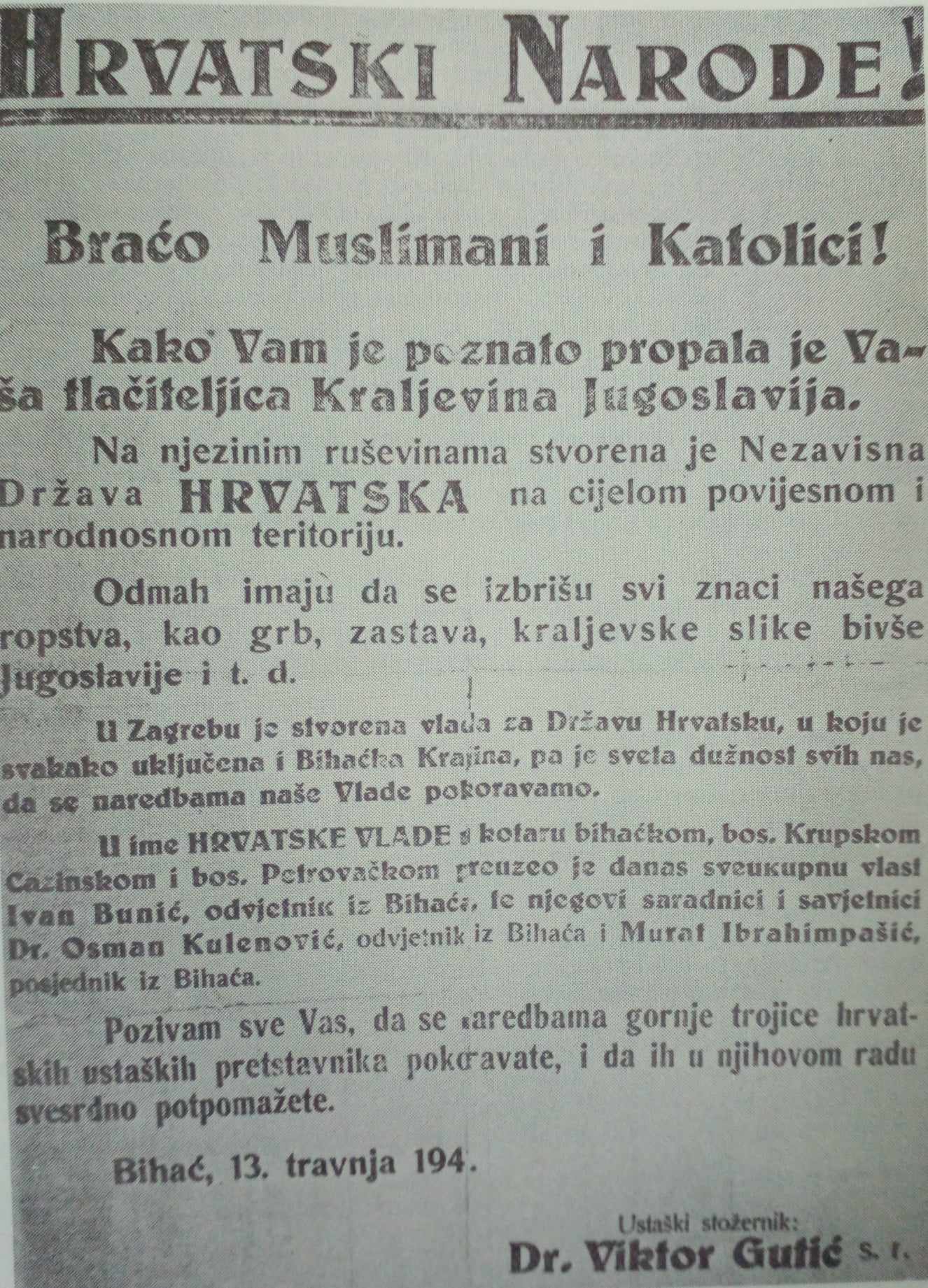

The establishment of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was met with enthusiasm not only by Croats but also by the majority of the Muslim population in the territory of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. Some among them dreamed of restoring the privileges they had enjoyed during the Ottoman occupation of the region. Elderly Muslims could be heard saying: “Serbs ruled long enough. Now it is our turn to govern!” Shortly after the NDH was established, some of the first murders of Serbs happened in Bihać by Ustashe Lieutenant Himzo Bišćević. Upon returning to his hometown of Bihać, he arbitrarily arrested Rade Dizija, a driver from the village of Meljinovac, along with peasants Petar Bojić and Budo Delić from the village of Ružica (now a neighborhood of Bihać), killed them and buried their bodies within the grounds of the military camp in Žegar.

Muslim Ustashe from the village of Kijevo near Sanski Most were involved in an incident that led to the first major armed resistance by Serbs within the territory of the NDH, known as the “Đurđevdan Uprising”. On May 6, 1941, a group of Ustashe from Kijevo, influenced by Husein Šabić Salihov, harassed Serbs in the villages of Srpsko Kijevo, Kruhari and Tomina. They entered homes allegedly searching for hidden weapons and, during Đurđevdan[1] celebrations, insulted and cursed the family patron saints, extinguished and threw away the feast candles and food and assaulted individuals—prompting the villagers to resist.

Many Muslim political and religious representatives supported and joined the government of the NDH, as did a significant number of Muslim intellectuals who made themselves available to serve the regime. On May 30, 1941, imam Smajil Mijakić, leading a delegation of Muslims from Bosanska Krupa, presented a Resolution to Pavelić on behalf of his congregation, which, among other things, stated:

„To you, Poglavnik, as the bearer of a new and fortunate era, we pledge our loyalty, ready to lay down our property and our lives with the conviction that, for us Muslims, after a period of hardship and barbarism, no happier hour has ever struck nor a more beautiful day come than the one when you, Poglavnik, assumed leadership of the Croatian people and state… All eyes are turned solely toward you, and from the depths of their souls, all pray to God to keep you healthy and strong, for the glory and pride of the Croatian people and our beloved homeland — the Free and Independent State of Croatia.”

Another imam, Bećir Borić from the Cazin area, was the main organizer and leader of Muslim peasants from that region who committed monstrous crimes in Serbian villages. Under the pretext of gathering Serbs for religious conversion, on August 9, 1941, imam Borić, together with his congregation, massacred over 200 Serbian peasants — their own neighbors — in the mixed Serb-Muslim village of Miostrah. The following testimony about the event was given by an eyewitness, Serbian woman Stoja Uzelac:

„The Ustashe surrounded us; they were armed with firearms, axes, scythes, stakes and other cold weapons. Suddenly, they opened fire on us, and then shouting and cursing followed:

‘Strike them, damn their Serbian mothers, strike the Serbian dogs!’

Then they charged at us from all sides. It wasn’t just the Ustashe with weapons — there were many civilians too, armed with axes, scythe blades, stakes and anything else they could use to strike us. I was hit by a rifle bullet, but I managed to stay on my feet. But when I saw one of the criminals kill my mother with an axe, I fainted.”

Under the leadership of Imam Borić, Muslims also attacked Serbs in other villages around Cazin. In addition to the killings of Serbs, cases of forced Islamization also occurred. In his memoirs, Dragan Grgić, a recipient of the “Partisan Memorial Medal 1941” – which are soon to be published by the “Forgotten Roots” Foundation under the title “Korana as a Wound” (Корана ко рана) – wrote the following regarding the forced Islamization around Cazin:

“A Muslim sits in the front, driving the horses, and behind him sits an imam. Wrapped around his head is his white amedija (turban) made of white cloth. This is imam Bećir Borić from the village of Miostrah, not far from the Una River, near Gomila. That imam Borić has so far participated in the massacres of women and children carried out in all Serbian villages throughout the region, such as Krndija and Bukovica. He personally slaughtered most of the victims. He organized Muslims from the surrounding area to gather Serbs in the villages under the pretext of protecting Islam and the Islamic faith, because it was observed that some Serbs, when forced conversions began, preferred converting to Catholicism over accepting Islam.”

Additionally, Serbs in the town of Cazin who were forced to convert to Islam were given a white armband with the word “Muslim” written on it, which they were required to wear — something reminiscent of the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany.

The mass killings of the Serbian population across the territory of the NDH during the summer of 1941 — particularly in late July and the first days of August — became known as the “Ilindan[2] Massacres”. This was a deliberate campaign aimed at exterminating the Serbian people. Exceptional brutality was displayed in the region of Bosanska Krajina. In addition to official Ustashe units, the massacres were also carried out en masse by “wild Ustashe”, name given to armed civilians from the local Croat and Muslim populations.

In the previously mentioned town of Bihać, during the summer of 1941, several thousand Serbs were killed. The largest execution sites in Bihać were the Garavice massacre complex, which consists of three locations (Garavice, Ceravci and Uljevite Bare), as well as the prison in the Bihać Tower (Bihaćka kula). According to some estimates, around 12,000 Serbs from Bihać and surrounding districts were executed at Garavice. On the other hand, the prison in the Bihać Tower was a site where Ustashe carried out brutal acts of torture on imprisoned Serbs. Disturbing examples of human cruelty have been recorded. For instance, Orthodox priest Ilija Tintor had his beard set on fire and one eye gouged out — the other left so he could see where his grave would be. One group of torturers was led by Derviš Meho Salihodžić, who, after mutilating the victims, would carry their ears and noses in his pockets. [6] Another individual known for his morbid role in the executions of Serbs in Bihać was Jusuf Pašagić, who admitted to having slaughtered around 200 Serbs.

In Sanski Most, during the summer of 1941, several thousand Serbs were killed. Members of the Muslim population played a significant role in these crimes. Serbs were murdered both in the town itself and in the surrounding villages. The largest mass executions took place at Šušnjar, in the Grain Warehouse (Žitni magacin), at Troska, in Čaplje, Vrhpole, Stari Majdan and other locations. These crimes also involved members of the Domobrani (Home Guard) forces, who ensured that Serbs who had taken refuge in the forests did not attempt an attack on Sanski Most. In Sanski Most, the Domobran unit was under the command of Teufik Silahić.

According to the testimony of Milan Miljević, when the killings of Serbs began at Šušnjar, Himzo Zukić, known as Ćiko, was the first to start with the killing. Among the Muslims who took a leading role in murder of Serbs at various execution sites in Sanski Most were: Hasan Bešić; five members of the Hasić family from Trnava — Latif, Hasan, Mujo, Himzo and Džafer; five members of the Kamber family from Pobriježje — Alija, Islam, Ćerim, Fejzo and Ibrahim known as Bućan; Muho Taraš; Began Suljanović from Halilovića Brdo; from Sanski Most — Husein Muhić known as Kiko, Hamdija Alagić known as Buljina, Mustafa Alagić, Mumin Heder, Ibrahim Nalić, Salko Kuršumović and Ferhat Krupić; from Kljevci — Ibro Kenjar and Mehmed Kazić; from Vrhopolje — Hasan Kerić and others.

Muslims in the Prijedor srez, in significant numbers, also took part in the Genocide against Serbs in the NDH. During the Ilindan Massacres, Muslims in the town itself, as well as in the Kozarac and Ljubija areas, carried out mass killings of Serbs — often using cold weapons. Civilians participating in the murder of Serbs in Prijedor wore white armbands bearing the NDH insignia so they would not be mistaken for Serbs. At mass execution sites near Kozarac, local Muslims under the leadership of Husein Mujagić killed several hundred Serbs from nearby villages without firing a single bullet. Throughout the entire Second World War, Kozarac remained a strong Ustashe stronghold. There, too, neighbors killed neighbors:

“And then our neighbors came — the Melkić, the Mahmujlin, the Hodžić, the Bešić — and they asked: ‘Where is your Nikola?’…When he arrived, they immediately gathered and started beating him…They didn’t even have firearms…Then they dragged them with horses and didn’t allow our women to bury them — instead, they were buried in a Muslim-owned field…”

In Ljubija as well, there were cases of women being humiliated while trying to bury their husbands and relatives:

“When all the Serb men had been killed, I went to Mustafa Bašić, the barber, to beg him to let us go to the cemetery, to let us move all our loved ones there and to mourn them at their graves. He told me we could go, so we did — but we were not allowed to cry… We had to go all together, and we were followed from both sides by Ustashe, among them Ibrahim Čehić and many others…”

The extent to which the killing and looting of Serbs had escalated in certain areas is also reflected in a partisan proclamation addressed „To All Residents of the Municipalities of Ljubija and Suhača and to All Honest Muslims and Croats,“ calling for an end to attacks on Serbian villages. Otherwise, it warned, all Muslim and Croat villages “participating in the looting, burning and killing of innocent Serbian civilians will be burned down and not a single stone will be left standing.”

In the Prijedor srez, around 1,500 Serbs were killed over the course of just a few days during the Ilindan Massacres. In addition to Muslims and Croats, Serbs in Prijedor were also killed by Muslim Roma. According to testimonies of those who escaped Prijedor and fled to Serbia “Gypsies and Muslims even pulled gold teeth from the corpses.”

In other parts of Bosanska Krajina where Muslims made up a significant part of the population, members of that group also committed mass crimes against Serbs in the summer of 1941. Some of the most notorious areas for such atrocities were Bosanska Krupa, Bosanski Novi, Velika Kladuša, Kulen Vakuf, Bosanski Petrovac, Bosanska Dubica and Bosanska Kostajnica. Survivors noted that among the Ustashe and armed Muslim civilians, there were even children as young as 12 who participated in looting Serbian property — such as on August 22, 1941, in Stabandža near Velika Kladuša:

“Twelve-year-old children were among them. All were armed with rifles, hoes, scythes, pitchforks and other tools.”

In the Bosanska Krupa area, Serbs were killed at multiple locations and in surrounding villages. Near the Sokolski Dom (Sokol House), executions were carried out by, among others, the following Ustashe: Selman Grošić from Potkalinje, who was the main executioner; then First Lieutenant Himzo Hadžić, Adem Beširević, Murat Halik, Fetahbeg Krupić, and others. The killings lasted from July 24, when the first arrests began, until August 4. In addition to Muslims from the town itself, Muslims from Otoka, Jezerski, Bužim, Bušević and Pištaline also participated in the massacres of Serbs during those days. Some of the identified executioners included: Husnija Omerčehajić, a barber from Otoka; Ibrahim Bešić, a baker; Đemo Ramić, Mustafa Bratić, Kasim Bešić, Kušim Mujagić, Ethem Bešić, Muhamed Bratić, student Husein Suljić and butcher Avdaga Komić — all from Otoka. In contrast to the Muslims, the Croats from Otoka did not participate in these crimes. The Ustashe camp commander in Otoka was Avdo Mujagić, one of the main organizers of the massacres. During those days, several thousand Serbs from the Bosanska Krupa area were executed.

In Bosanski Novi and its surroundings, Muslims were far more numerous than Croats and took it upon themselves to „solve the Serbian question“ and seize Serbian property. During the Ilindan Massacres in this srez, over 1.000 Serbs were killed. The perpetrators were most often Muslims from the town itself, but also from surrounding villages such as Suhača Hozići, Blagaj Japra and others. Alongside the Sixth Ustashe Battalion, which was composed mostly of Muslims and Croats from the Bosanski Novi area, various Muslim formations also operated — such as Nogo’s Militia based in Suhača.

Some of the identified perpetrators included: Karanfil Halilović, Alaga Ćorić, Ahmet Šabić, Asim Krajisković, Sanija Isaković, Smajl Bečić-Ekić, Suljan Vanić, Salih Kantar, Ibrahim Ekić, Ale Fetibegović, Salih Barjaktarević, Jusuf Vakufac, Husein Vakufac, Selim Zdionica, Jusuf Bumić, Dedo Isaković, Muharem Zdionica, Ahmet Talić, Ibrahim Nezić, Dedo Selmić, Ibrahim Selmić, Sulejman Silić, Hakija Selmić, Arif Selmić, Dedo Mehmedagić, Emin Šumić, Himzo Velić, Mustafa Alibašić, Rasim Arapović, Hasan Velić, Hasib Pašić, the imam from Suhača — Bego Barjaktarević, Musem Isaković, Dedo Isaković and others.

The Serbian villages around Kulen Vakuf were also targeted by local Ustashe and armed civilians, many of whom were Muslims. On July 1, Ustashe from the Donji Lapac area killed around 300 Serbs in the village of Suvaja. On July 2, in the village of Osredci (Lički Osredci), Ustashe murdered 13 Serbian peasants, while most of the villagers had already fled into the forest. On July 3, the Ustashe from Donji Lapac were joined by their neighbours from Kulen Vakuf. These combined Ustashe forces launched an attack on the village of Bubanj (Donji Lapac), killing around 270 Serbs. A large number of the bodies were burned. A military report from the NDH recorded that “Muslims from Kulen Vakuf also arrived and were particularly involved in looting livestock from barns and pastures, as well as removing belongings from homes.”

According to accounts from surviving Serbs from Bubanj, they were deeply shaken by the behaviour of their neighbours: “These were our neighbours to whom we used to offer help… (but now) they no longer feel anything toward us. Their only desire is for Serbs to disappear, to seize our property, to store Serbian grain in their own hangars”.

During July, Ustashe from Kulen Vakuf launched attacks on surrounding Serbian villages. By the time the Serbian uprising began on July 27, 1942, witnesses reported that Ustashe from Kulen Vakuf had killed the following: in the village of Rajnovci (in mid-June), 27 people, and captured another 18 on the roads; in the village of Oraško Brdo, 36; in the village of Velike Stijene, 9; and in the village of Prkosi with Čovka, 16, among others.

At the end of July, insurgents ambushed a column of 150 Ustashe sent from Kulen Vakuf toward the village of Čovka. Twenty Ustashe were killed, and 13 rifles were captured — a highly valuable prize for the poorly armed rebels at that time. The calloused hands of Serbian peasants had taken up rifles to plow the furrows of freedom. When Serbian insurgents drove the Ustashe out of Kulen Vakuf in late August 1941, they discovered a mass grave containing around 950 Serbian corpses. This discovery led to acts of revenge, not only against captured perpetrators but also against civilians.

Some of the names of Ustashe from Kulen Vakuf are: Avdo Buržić (Kulen Vakuf), Bego Kadić (Kulen Vakuf), Ahmet Kadić (Kulen Vakuf), Mahmut Kadić (Kulen Vakuf), Huća Zelić (Kulen Vakuf), Meho Mušeta (Kulen Vakuf), Mustajbeg Kulenović? (Kulen Vakuf), Reuf Kurtagić (Kulen Vakuf), Hilmija Altić (Kulen Vakuf), Hurija Altić (Kulen Vakuf), Mumaga Mehadžić (Kulen Vakuf), Mahmut Kulenović (Kulen Vakuf), Ibrahim Pehlivanović (Kulen Vakuf), Muho Bibanović (Kulen Vakuf), Muho Islamagić (Kulen Vakuf), Agan Kozlica (Orašac), Bego Kozlica (Orašac), Kozlica Huso (Orašac), Alago Rusadžić? (Orašac), Mujago Šušnjar-Vukalić (Orašac), Adem Kulenović (Orašac), Esad Hukić (Orašac), Ramo Glumac (Orašac), Osman Glumac (Orašac), Redžo Hadžić (Orašac), Ibrahim Vojić (Orašac), Behram Džafica (Orašac), Alija Bašić? (Orašac), Meho Mešić? (Orašac), Ahmet Ramula Bećin? (Orašac), Husein Mešić (Orašac), Mešić Suljo (Orašac), Orić Rasif (Orašac), Šabeg Redžo (Orašac), Karpush Džađo (Orašac), Hodžić Islam (Orašac), Šabetić Redžo (Orašac), Šabetić Džafica (Orašac), Kajić Ibrahim (Orašac), Kajić Rasif (Orašac), Mušetić Džađo (Orašac), Alibakčević Adem (Orašac), Stupac Sulejman (Orašac), Stupac Husein (Orašac), Hrnjica Ibrahim (Orašac), Kulenović Reuf (Kulen Vakuf), Vajić Ahmet (Orašac), Vajić Muho (Orašac), Delić Huso (Orašac), Delić Muho (Orašac), Vajić Kadrija (Orašac), Vajić Velaga (Orašac), Mušeta Džaja (Orašac).

Muslims were aware that in Bosanska Krajina, the power of the NDH rested largely on them. For this reason, representatives of the Muslim community in Prijedor complained to Muslim leaders within the NDH hierarchy about the low rate of Muslim employment in the civil service, even though “after the expulsion of the Serbs, there were enough vacant positions,” and that “over 75% of all Home Guard soldiers and officers of the Croatian army in Bosanska Krajina are Muslims, and they bear the greatest burden in maintaining the survival of this state.” According to certain estimates, Muslims made up over 50% of the total number of Ustashe in NDH units operating within the territory of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina.

When the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) succeeded in bringing most of the Serbian insurgents in the Bosanska Krajina region under its control and forming partisan units, Muslims overwhelmingly ignored the call to join the Partisans during the early years of the war. Although the communists emphasized their fight for “brotherhood and unity”, accused the pre-war monarchy of oppressing Muslims and Croats and promoting Serbian hegemony, and although they claimed to be fighting against the Chetniks as well, Muslims generally preferred to remain in NDH formations or kept a reserved distance. As a result, by the end of the war, Muslims had contributed more to the survival of the NDH than to the struggle for the freedom of all peoples — or what is today commonly called anti-fascism.

The words of a Muslim peasant, recorded in a partisan report from November 1943, vividly reflect the general Muslim attitude toward anti-fascism:

„Why are you pressuring us to join the army? It’s enough that we’re not fighting against you. Just leave us alone.“

During all major offensives by Croatian and German forces against Partisan-held territories in Bosanska Krajina, members of the Muslim population took part in the fighting as soldiers in the Domobranstvo (Home Guard) or the Ustashe, and often also as members of local Ustashe militias. It was recorded that during the large German-Croatian offensive on Kozara in 1942, Muslims from Kozarac looted abandoned Serbian villages:

“There was widespread looting in the villages around Kozara, and everything that could be found was taken away. The Muslims from Kozarac even stole construction materials.”

There were some cases of Serbs managing to escape from Kozara and return to their villages. Those who relied on help from their Muslim neighbours were often deceived. For example, a young man named Miro Nenadić from Gornji Garevci, after returning to his burned-down household, asked the Grozdanić family—his neighbors—for help. Instead of helping him “Ahmed Grozdanić and his relatives Behlil and Halil Grozdanić, along with Meho Majdanac and Ale Selimović, took” Nenadić to Kozarac, where he disappeared without a trace.

Muslims also took part in the extermination of Serbs within the death camps established by the NDH. According to eyewitness testimonies, there were units within the Jasenovac camp complex that included Muslims. The 49th Ustasha Company, composed of Muslims, was deployed from the town of Jajce and its surroundings to guard Jasenovac. Among the most notorious executioners in Jasenovac, individuals known as Mujo and Šaban were identified.

There were also instances where Muslims came to devastated Serbian villages under the pretence of helping surviving civilians with ploughing and similar tasks, all organized by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ). However, after completing the ploughing, they would sometimes bring Ustashe to finish off the remaining Serbian civilians who had survived earlier massacres. One such case occurred in Serbian villages near the Muslim village of Orahovac, located between Kozarska Dubica and Gradiška. Slavko Đekanović, born in 1929 in Međeđa near Bosanska Dubica, testified about these ploughmen from Orahovac in 1943:

“The Partisans mobilized those Muslims from Orahovac along with about ten wagons to help the people plough and plant some gardens. They stayed for five or six days and then left. Another shift of Partisans was supposed to arrive. The very next morning, the Ustashe attacked from the forest. They were led by those same Muslims who had been here ploughing. They told them everything — where everyone was… That morning, they found children and women and slaughtered them. There were both refugees and local people from the village. They weren’t killed with firearms — they were slaughtered!”

This is only a small portion of the examples that point to the participation of Muslims from Bosanska Krajina in the Genocide against Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH). Today, there is an ongoing attempt to deny these crimes against Serbs or to attribute them solely to Croatian Ustashe or vaguely defined „fascists“. Official Sarajevo seeks to promote the narrative that Muslims were overwhelmingly on the side of anti-fascism, that they helped Serbs and that they did not accept the NDH as their state.

However, beyond the extensive evidence of direct Muslim participation in the Genocide against Serbs in the NDH, there are also testimonies from Muslims who were members of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and the Partisan movement. One of them, General Hamdija Omanović, stated at the Third Session of ZAVNOBiH (The State Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Bosnia and Herzegovina) on April 26, 1945, in Sarajevo:

“We Muslims must admit that the vast majority of Muslims found themselves on the side of the occupier.”

[1] St. George feast day

[2] St. Elijah feast day

Скорашњи коментари